Operation SILVERPLATE

The Aircraft of the Manhattan Project

By George Cully, IPMS #2290

August 1995 marked the fiftieth anniversary of the dropping of the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. But you probably already knew that. The two Boeing B-29 Superfortresses involved, Enola Gay and Bock's Car, are both in museums. The issue of how to display the Enola Gay has become something of a political hot potato for the Smithsonian's National Air & Space Museum. But you probably already knew that, too.

The simple fact is, even if your modeling interests favor something other than WWII aircraft, it's hard NOT to have heard about these two planes - a huge literature has developed about their missions, and about the Manhattan Project in general. What follows is a brief survey of the aircraft used in the course of developing and delivering the first atomic bombs. Much of the information is available in published sources, but some lesser-known details come from declassified records held in various government archives.

HOW TO BUILD A BOMB

The Army Corps of Engineers established the Manhattan Engineering District in June 1942 to oversee the design and production of atomic bombs. The following winter, Brigadier (later Major) General Leslie Groves and Dr. J. Robert Oppenheimer chose a secret research site in the mountains of northern New Mexico - a remote mesa then owned by a boarding school called the Los Alamos School for Boys. For the next three years, the well-guarded compound at Los Alamos hosted the greatest single gathering of scientific genius in history.

By the spring of 1943, Los Alamos' theoreticians were ready to give shape to the weapon their calculations had proven possible. The Manhattan Project scientists knew that there were several "active" elements particularly well-suited for making atomic bombs - an isotope of uranium (U235), and plutonium, an 'artificial element made by bombarding uranium with neutrons in a nuclear reactor. Huge plants for separating U235 were already under construction at Oak Ridge, Tennessee, and plutonium reactors were being built on the Columbia River near Hanford, Washington.

The Los Alamos team had also looked at various ways of assembling active materials to make a weapon, but they focused upon two specific means of reaching 'critical mass' - the minimum amount of active material required to achieve a nuclear detonation. The less complicated of the two techniques was called the 'gun method. It requires one piece of active material to be loaded into a cannon and fired into another piece mounted in a plug in the cannon's muzzle. The idea is that the two smaller pieces will combine to form a critical mass and stay intact long enough to detonate before the pent-up propellant blows the cannon barrel and its contents apart.

Gun-assembly is the simplest and most reliable way to combine several sub-critical masses of active material, but some Los Alamos theoreticians had also considered implosions almost from the outset. That method uses explosives to squeeze a single, subcritical mass so that it becomes dense enough to 'go critical' and chain-react into full-scale detonation. Implosion demands very precise timing and extreme reliability because the inwardly-focused explosions must achieve near-perfect symmetry; their shock waves all have to converge upon the nuclear core at exactly the right time, so that it will be compressed to the same degree on every point of its surface. Manhattan Project analysts compared this extremely difficult process to crushing an unopened beer can without spilling any of the beer, and it wasn't until the fall of 1943 that implosion actually seemed achievable.

In the summer of 1943 the Los Alamos team expected that plutonium would be the active material used in the combat weapon, and they assumed that the gun method would be used to assemble the bomb's active components. Even so, they knew that plutonium's rate of spontaneous natural fission would require the gun to have a muzzle velocity of about 3,000 feet per second - anything slower risked a drawn-out, low-yield reaction that would waste most of the plutonium's energy potential. Ordnance designers' calculations showed that accelerating the plutonium projectile to the necessary speed would require extraordinary propellant pressures. Even with the use of special steel alloys, the gun barrel would still need to be at least 17 feet long to do the job. How would a bomb of such length perform when dropped from an airplane?

EARLY FLIGHT TRIALS AT NPG DAHLGREN

If the Manhattan Project was to succeed, it had to do more than simply build atomic bombs. It also had to fashion a reliable means of delivering those bombs to the enemy. Overall management of atomic weapon delivery was placed in the capable hands of Captain William S. 'Deke' Parsons, USN, and Dr. Norman F. Ramsey. Parsons had been a major player in getting the proximity fuze out to the fleet. Ramsey, a gifted physicist and engineer-organizer, would be the 'fixer' responsible for running day-to-day operations.

The first scale models of the plutonium gun bomb were fashioned by simply cutting a standard 500 pound aerial bomb in half and splicing a length of sewer pipe in between. Test drops were made from a Grumman TBF beginning in August 1943 at the Naval Proving Ground (NPG) range near Dahlgren, Virginia, but the ballistic characteristics of the 'sewer pipe bomb' were truly awful. Upon release, the bomb invariably went into a flat spin and broke up when it hit the ground broadside. Even as revised scale models of the plutonium gun continued to be flight-tested at Dahlgren, however, Norman Ramsey was beginning to scout out a suitable carrier aircraft for the full-sized weapon.

In 1943, there were no aircraft in the US inventory with a bomb bay that could contain a 17 foot bomb. Ramsey did consider modifying a Consolidated - Vultee B-24 Liberator bomber for the purpose, only to abandon the idea when he discovered that the Navy had already tried to reengineer the B-24 for internal torpedo carriage and failed. That left the Boeing B-29 as the only other possible American candidate. During a field trip in August, Ramsey made surreptitious measurements of the Superfortress. He found that it could be adapted for the purpose by combining its two 12 foot bomb bays into one, but only if the bomb was no more than two feet in diameter. The reason was that the two bays were separated by the wing spar carry-through box, and the maximum distance between the lower side of the box and the bottom of the fuselage was no more than two feet.

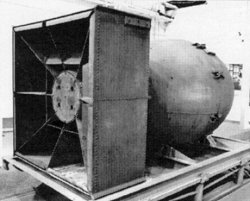

MS-469: THIN MAN, FAT MAN, AND THE SILVER PLATED PULLMAN

By the late fall of 1943, the ballistic problems of the plutonium gun bomb had been largely solved with improved tail surfaces and better weight balance. As its internal arrangements became more firmly established, the casing's layout was modified to follow suit. The final 'pod' or Cornog model (named after a design team member) featured a rounded, bulbous nose to house the fuzing arrangements and the muzzle plug - the 'anvil' - that was to hold the plutonium target, and a long, slender body with an elongated box tail. The full-size models were 18 feet long, and the design team estimated that the final product would weigh about 7,500 pounds.

Scale model air-drops continued on into the winter at Dahlgren, but it had become obvious that another site was needed. The air near Chesapeake Bay was hazy, and full-sized model testing would have to be conducted from as high as 30,000 feet; good visibility was important. But security was also a concern - there were too many curious eyes in eastern Virginia. Parsons and Ramsey began searching for an alternative test site. In the meantime, Los Alamos scientists and engineers had also made progress in working out the practicalities of an implosion bomb. Its arrangements would be quite different from the plutonium gun weapon, however, and that meant that the search for a suitable bomber had to be expanded. In September, Ramsey was instructed to find an aircraft with a bomb bay that could carry a weapon weighing as much as 9,500 pounds. Unlike the long, slender plutonium gun, this new bomb had to be ball-shaped to contain the bulky explosive charges; Los Alamos' best guess was that the new design could be up to six feet in diameter.

Ramsey quickly concluded that there were only two Allied bombers capable of carrying both weapons: the Boeing B-29 (if suitably modified) and the Avro Lancaster. The Lancaster had ample room internally, and it was a prodigious weight lifter; it almost won the contest. In fact, Ramsey traveled to Canada in October 1943 to meet with Roy Chadwick, the Lancaster's chief designer. As luck would have it, Chadwick had crossed the Atlantic to view Lancasters being built at the Avro Canada works in Toronto, and Ramsey seized the chance to show Chadwick some preliminary sketches of both the gun and the implosion weapon casings. Chadwick assured Ramsey that the Lancaster could accommodate either bomb and promised whatever support might be needed, but he was well-used to wartime secrecy; Chadwick did not ask why the weapons had such unusual shapes.

When Ramsey returned to the US, he recommended to Parsons that the Avro Lancaster should be seriously considered. Apparently General Groves had not yet asked for US Army Air Forces support, however, and a different kind of detonation took place when the Chief of the USAAF, General H. H. 'Hap' Arnold, received word of the proposal. Arnold had been personally briefed on the programs importance by the Army Chief of Staff, but Arnold made it clear to Groves that, if any atomic bombs were to be dropped in combat, a USAAF-crewed B-29 would deliver them. With that proviso firmly established, Arnold willingly endorsed the Manhattan Project's request for USAAF assistance.

On 29 November 1943, a team of USAAF and Manhattan Project representatives met at Wright Field, Ohio, to work out the details for modifying a small number of B-29s to carry atomic weapons. The USAAF was to modify the first aircraft and turn it over to the Project by 15 January 1944; a small number of combat-ready aircraft would follow later. For its part, the Manhattan Project agreed to send technical representatives and two full-sized examples of the plutonium gun weapon (code-named THIN MAN) and the implosion weapon (codenamed FAT MAN) to Wright Field by mid-December. The following day, instructions were sent to the AAF Materiel Command to modify a B-29 at Wright Field for a project to be held in greatest secrecy, code-named SILVER PLATED. In turn, AAFMC's engineering Division issued the work a separate internal code name, PULLMAN and a classified project reference number, MX-469. The word PULLMAN had been chosen to fit the overall cover story devised on 29 November: British Prime Minister Churchill (the FAT MAN) would visit the US to tour defense plants with President Roosevelt (the THIN MAN) in a specially-modified (SILVER PLATED) B-29 (the PULLMAN). With usage, the overall code name was soon shortened to its more familiar form: SILVERPLATE.

Boeing-Wichita completed its fifty-eighth B-29, AAF serial number 42-6259, on 30 November 1943. The airplane was delivered to Salinas Field, Kansas that day, and it was in Wright Field's modification shop two days later. The revisions were done 'by hand,' and consumed over 6,000 man-hours. The belly skinning was removed between the two bomb bays to make one long opening, and the four 12-foot bomb bay doors were replaced by two 27-foot doors. The rear bay's forward bomb racks were fitted with a carrier frame and sway bracing, and hoists were mounted at each of the four corners of the frame. Dual release mechanisms were adapted from glider tow equipment and fitted fore-and-aft to the carrier frame, and motion picture camera mounts were added to the rear bay. The THIN MAN shape fit but, as expected, with very little clearance: its 'pod' nose was 23 inches in diameter. The modification process took until early February, and engine troubles further delayed the airplane's availability; it didn't arrive at Muroc Field (now Edwards AFB), California until 20 February 1944.

FLIGHT TRIALS AT MUROC

The first flight test drop at Muroc - a standard THIN MAN - took place on 6 March, followed on 14 March by two FAT MAN shapes fitted with circular tail shrouds designed by engineers at the National Bureau of Standards. The THIN MAN worked well; its ballistics had been largely ironed out during the previous scale model tests at Dahlgren. On the other hand, the FAT MAN shapes performed poorly, demonstrating yaw ('wobble') angles of as much as 19 degrees; the problem was attributed to poor workmanship and misalignment of the tail surfaces.

The use of glider tow releases also proved to be a major problem. All three bombs failed to release immediately, leading the calibration efforts completely awry. A fourth drop test, scheduled several days later, resulted in a premature release while the B-29 was still enroute to the test range. The 7,300 pound THIN MAN fell on the bay doors and severely damaged them; the plane had to be sent to San Bernadino for repairs. The consensus was that the twin release lugs were at fault, and the test team successfully argued that the Project should adopt the British method of suspending heavy bombs by a single lug.

Testing resumed in mid-June, and twelve shapes were dropped from 42-6259 between the 14th and the 27th: three THIN MEN and nine FAT MEN. Various combinations of tail boxes and drag fins were tested on the implosion shape, all in an effort to dampen the device's persistent wobble. The solution that was finally adopted combined a box tail with internal drag plates set at 45 degrees to the line of flight; the test team called this arrangement a 'California Parachute.' As an interesting sidelight, the analysts reported that the tracking films were showing a very high failure rate for standard tail fins on USAAF aerial bombs - perhaps as many as one in four fin sets was seen to collapse as the bomb reached terminal velocity, with an obvious and drastic effect upon the bomb's accuracy. This information was passed on to General Groves with the assumption that the Ordnance Department would very much want to know of the failures. Groves reportedly suppressed the data in the belief that Project security would be compromised if it was released, and the Ordnance Department didn't discover the problem for another year.

THIN MAN BECOMES LITTLE BOY

Previous theoretical studies had identified a possible problem with gun-assembled plutonium weapons. When the first Hanford-produced plutonium samples arrived at Los Alamos in the spring of 1944, that 'possible problem' turned out to be a show-stopper. To make plutonium meant 'cooking' uranium in a nuclear reactor. Unfortunately, the same process that made plutonium also created impurities in it, and those impurities could not be removed by chemical means. The impurities raised the 'fissionability of Hanford-produced plutonium such that NO gun could shoot pieces of it together fast enough; they would begin to interact well before they could be fully joined. THIN MAN was a dead end.

As it turned out, the failure of THIN MAN was a blessing in disguise As a hedge against the failure of implosion - still not a sure thing in the spring of 1944 - the gun model was revamped to use U235 instead of plutonium. U235 fissions less efficiently than plutonium, but there was an advantage to this approach in that the assembly speed could be greatly reduced. In turn, by lowering the gun's muzzle velocity to 1,000 feet per second, the barrel length could be reduced to less than ten feet - and that would fit the gun weapon into a standard B-29 bomb bay quite nicely.

SILVERPLATE MOVES TO WENDOVER

As the summer of 1944 progressed, the expanding test program and the need to form a combat unit argued strongly for the acquisition of more SILVERPLATE airplanes. On 22 August, 24 SILVERPLATE-modified B-29s were ordered from the Glen L. Martin Modification Center at Omaha, Nebraska, with the first three aircraft to be delivered by 30 September, followed by 11 more by 31 December. These 14 aircraft would be used for test and training purposes. The remaining 10 were due "as soon as possible" in 1945; outfitted with the latest changes, they would be reserved for combat.

Given that Muroc did not have the facilities necessary to support 12 to 14 B-29s and the 500 to 650 people needed to operate and maintain them, the Project was persuaded to pick another site for training. Like Muroc, it needed to have clear weather, and it needed to be just as isolated for security purposes. Wendover, Utah fit the bill perfectly. In addition to a site selection, the combat unit was identified and its commanding officer selected: the 393rd Bomb Squadron, a part of the newly-activated 504th Bomb Group (Very Heavy). The 393rd was detached from the 504th without explanation and assigned to a new unit, the 509th Composite Group. Another flying outfit, the 320th Troop Carrier Squadron, was also assigned so as to provide the Group with its own internal airline. Because of their signature paint scheme, the 320th's five C-54s were called the Green Hornet Line Practice missions, strict security, and 'need to know' quickly became the 509th's daily bread. Only the Group's commander, Colonel Paul W. Tibbetts, Jr., knew its mission.

In mid-October, the first three of the new SILVERPLATE aircraft batch (42-65209, -216, and -217) were accepted from the Martin-Omaha facility. Unlike 42-6529, the original PULLMAN airplane, they were fitted with a single-point bomb release modeled after the British 'Type F' heavy bomb mechanism and mounted on an improved frame fitted in the forward bomb bay. Long range fuel tanks could be carried in the rear bay, and a new crew position, equipped with an elaborate monitoring system, was added to support the test program, and to prepare the bomb for release and detonation during the actual combat drops. In recognition of these new, complex duties, the additional position was called a 'weaponeer station.'

Training and test work began in parallel at Wendover immediately upon arrival of the 509th and continued through the winter and on into spring. Long-range missions were flown to test facilities established at Naval Weapons Station Inyokern, California, and later to ranges south of Albuquerque. The FAT MAN design evolved considerably in sophistication, although its ballistic characteristics still remained less than satisfactory. The new LITTLE BOY design also underwent continued development, but it had far fewer teething problems than FAT MAN.

PROJECT ALBERTA

Project Alberta was formally established within the Manhattan Project in March 1945, although its functions had been performed by various Project offices for months. Put simply, Project Alberta's purpose was to undertake the steps necessary to deploy the bomb into the combat zone, and to ensure that it was ready for delivery at the earliest possible moment. That meant training bomb assembly teams and technical support personnel, providing logistic arrangements for the 509th's special weapons, and assembling and testing weapons and practice devices in the forward area.

One major consideration was the state of readiness of the strike aircraft. Although the original order for the 'replacement' aircraft had specified ten planes to be delivered at a rate of two per month, by January 1945 it was clear that a piecemeal approach would not serve the 509th very well. The 'state-of-the-art' had rapidly overtaken many of the planes delivered to Wendover in the fall, and Colonel Tibbetts had made sure they flew as many hours as maintenance would support. In short, the 509th's airplanes were worn out. In February, the standing order for modified airplanes was doubled from a total of 24 to 48, and in April, five more were added to the order. The delivery schedule called for 13 aircraft to be delivered to the 509th in April, and two more per month for the next four months. (In all, 54 SILVERPLATE aircraft were ordered before V-J Day, but only 46 were actually completed and delivered.)

These new airplanes included all of the latest technical changes made to recent B-29 aircraft, as well as special modifications added only to SILVERPLATE aircraft. In addition to the special equipment related to carrying and dropping atomic bombs, the latest SILVERPLATE batch received fuel-injected engines and reversible-pitch propellers. Given that the final versions of the FAT MAN and LITTLE BOY weapons each weighed about 10,000 pounds, significant efforts were made to reduce aircraft weight. All the turrets were removed, as was a substantial amount of armor plate. As a result, the SILVERPLATE aircraft were slightly faster, achieved better fuel economy, and could carry a heavier payload at higher altitudes. Ramsey subsequently wrote that "...the performance of [the 509th aircraft] was exceptional ... they were without doubt the finest B-29s in the theater."

Deployment of key people to Tinian, including Parsons and Ramsey, was completed by the third week of July, and the first LITTLE BOY practice bomb, L1, was assembled and dropped on 23 July. Four more LITTLE BOYs were assembled and test-dropped before the Hiroshima mission on 6 August. The first test FAT MAN, F13, was dropped on 1 August. Three additional FAT MEN were dropped before the Nagasaki mission on 9 August. In addition, the 509th carried out many practice missions, both over nearby waters, and against Japanese targets. A practice bomb of about the same weight and ballistics as FAT MAN was provided for these missions, and it was nicknamed a PUMPKIN because of its coat of orange paint; PUMPKINS were filled with conventional explosives.

OPERATION CENTERBOARD

The two atomic strikes on Japan - code-named Operation CENTERBOARD - have been well reported. LITTLE BOY, weapon number L11, was dropped on Hiroshima on the morning of 6 August; FAT MAN, weapon number F31, was dropped on Nagasaki three days later. FAT MAN F32 was held in reserve for the third strike, should President Truman direct its accomplishment, and 20th Air Force targeteers were reportedly preparing for a night-time strike on Tokyo when the stand-down order arrived. The records are not entirely in agreement, but there is some evidence suggesting that the nuclear core for F32 was dispatched from Albuquerque on the evening of 12 August, and that the aircraft was half-way to Hawaii when it received the return order. Fortunately, no further strikes were necessary.

SILVERPLATE BECOMES SADDLETREE

After the war, the USAAF demobilized so rapidly that, within a year, it had become virtually ineffective as a fighting force. So debilitated had long-range bombing units become, in fact, that in early 1947 the Strategic Air Command found itself unable to identify the precise location and condition of all its SILVERPLATE airplanes. As a result, inspectors were sent out to track down and physically examine all of the aircraft remaining in the SILVERPLATE fleet. So many modifications and changes - some documented, others not - had been made that no two aircraft were identical. Drawings and paperwork had been discarded or misplaced, and new engineering materials would have to be drawn up from scratch before further improvements could be incorporated. Even the very name SILVERPLATE had become compromised through overuse and carelessness. To mark renewed emphasis on security, the USAAF's atomic weapon program ceased to be called SILVERPLATE on 12 May 1947; henceforth, a new codeword, SADDLETREE, would take its place.

George Cully is former President of IPMS-USA and also former President of IPMS/Albuquerque.